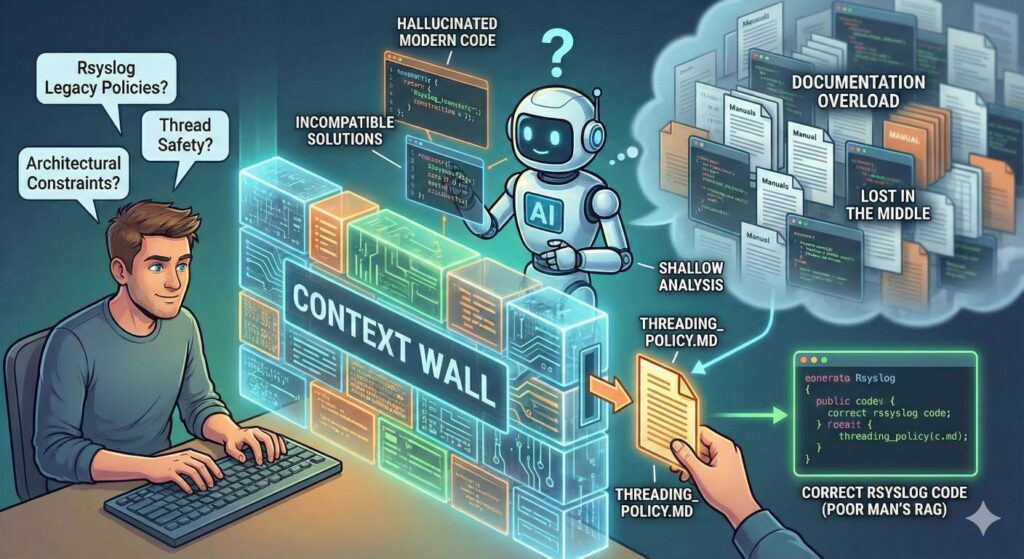

The ultimate promise of AI agents in software development is autonomy. We want to be able to hand off a task and have the agent execute it reliably. However, in my recent experiments with AI-driven code generation, I’ve hit a recurring roadblock: The Context Wall.

My goal is to make the agent run as automatically as possible. Unfortunately, as the documentation and necessary context for a specific task grow, reliability drops. The documentation simply becomes too large to be reliably injected into the context for related questions, leading to sub-optimal code generation and shallow analysis.

The Complexity of Maturity

This problem is magnified because rsyslog is not a typical modern web app. It is a mature C project where some code and interfaces have evolved over decades. We have strict policies on compatibility and thread safety that don’t always align with modern “clean slate” coding trends.

For an AI agent, this is a nightmare scenario. It’s not enough to just “know C”; the agent needs to understand years of architectural decisions and specific interface constraints that exist for good historical reasons. When the context window is flooded, the agent tends to hallucinate “modern” solutions that are technically valid C code but functionally broken within rsyslog’s ecosystem.

The “Hint Prompt” Workaround

Currently, I can cure these hallucinations by providing human help via “hint prompts.” While this works, it defeats the purpose. If I have to constantly guide the agent through the documentation I already provided, we aren’t achieving automation; we are just shifting the manual labor from writing code to writing prompts.

Observations from the Field

I have observed this behavior across several major tools, though the transparency of why it happens varies.

- ChatGPT Codex and GitHub Copilot: I have seen this clearly by following their reasoning steps and shown actions. It is distinct and observable when they drop context or fail to parse the relevant section of the documentation. Interestingly, while both are most probably driven by a very similiar engine, they behave somewhat different (even if using the same openai model).

- Google Jules: The same seems to happen here, but the interface is less transparent, making it harder to pinpoint exactly where the reasoning fails compared to the others.

- Google Antigravity: I have also begun to use this. It seems promising after some hours of use, and offers better insight into file access than Jules, but strict rate limits are currently preventing a full evaluation.

A concerning pattern: From my testing, it looks like the agents are surprisingly stingy with files. It appears that the number of files automatically included in the context is often smaller than I expected. I do not yet know exactly what causes this—whether it’s an intentional token-saving strategy or a retrieval failure—but the result is that critical policy files are often skipped.

I have not yet used Cursor. I suspect it might handle this better (it supports RAG-like constructs like @docs), but I want to avoid locking into a single vendor for now.

Next Steps: Refactoring Agent Docs

IMHO, one root problem is that many code agents do not have a robust RAG-type system for agent instructions or meta-information, nor the infrastructure to reliably call it.

As a continuous side-activity, I will try to refactor the rsyslog agent doc files. My goal is to check how much is possible within the bounds of the current systems by simply improving the data structure. I want to see if breaking down our massive documentation into “AI-friendly” chunks can trick these agents into retrieving the right policies automatically, without needing manual hint prompts or “Poor Man’s RAG” scripts.

Science Summary: Why this (probably) happens

For the technically curious, what I am observing likely intersects with two concepts in current Computer Science research:

1. Context Pruning (Hypothesis) Modern agents often use heuristics to manage their “Token Budget.” It is possible that the agents are performing a Reranking step—scanning available files and discarding those that don’t meet a strict relevance threshold. A policy file that doesn’t strictly match the user’s keywords might be “pruned” before the model even sees it.

2. The “Lost in the Middle” Phenomenon Research by Liu et al. (2023) has demonstrated that Large Language Models (LLMs) suffer from a “U-shaped” attention curve.

Models excel at recalling information at the start and end of a prompt, but information buried in the middle of a large context window is significantly more likely to be ignored. By refactoring the docs, I hope to make the relevant snippets “stickier” for the retrieval algorithms.